Review: Vancouver Writers Fest, Oct. 26, 2025

By Olivia Sherman

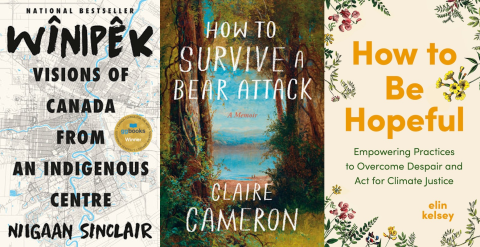

Never once have I heard of a book thanking the reader for picking it up off a shelf, but that’s how Elin Kelsey’s How to Be Hopeful chooses to start itself: a recognition, an acknowledgement, and an appreciation. With her background as a scholar and environmental educator, Kelsey discusses the ongoing conversation with young people regarding eco-anxieties and a looming fear of the future, and how many of the students she speaks with are stuck in the narrative that “hope is a privilege” regarding the climate crisis. She argues, however, that “hope is a choice… to confront any issue,” granting agency over the narrative that others want to write for you. Her how-to guide on avoiding “bathing in the narrative of doom and gloom” of the ongoing climate crisis sets up particular themes for the rest of the three-book event at 2025’s Vancouver Writers Fest, namely the inner strength and mindsets necessary for overcoming difficulties in the world, and in oneself.

Claire Cameron’s semi-autobiographical account of a bear attack in Algonquin Park in 1991 is an unconventional way of demonstrating those themes as well. Her latest book, aptly titled How to Survive a Bear Attack, covers Cameron’s personal story of loss and resilience in the backdrop of an unprecedented bear attack in a place she once considered a harmless refuge.

As a child, Cameron’s father passed away due to an aggressive form of cancer, and one of her outlets for this loss was to spend time outdoors in Ontario’s Algonquin Provincial Park. In 1991, two adults were killed by a black bear in the same park Cameron considered a second home, and the part-memoir, part-investigation covers the incongruity of that event. The memoir also covers the present, and Cameron’s current form of recurring skin cancer, the same one that took her father’s life years ago. “I’ve had cancer since, and I’ll have it again,” she says at the Vancouver Writers Fest, noting that her surgeon’s recommendation was to avoid sunlight. Much like the bear attack that shifted the security of the place she considered safe, her only outlet for overcoming times of struggle and grief is taken away from her. “Our built environments feel so convincing,” she says, noting the lack of certainty when those havens reveal themselves to be not as stable as one perceives. When your own body is ripe with cancer and your once-safe haven is tainted with the unprecedented and bloody loss of two lives, the memoir asks the question, “[h]ow does a reasonable person go about trying to be safe?” As Elin Kelsey states regarding her how-to guide, “it’s risky to believe in hope.” The risk-to-reward ratio when one chooses to hope above all else is wide, but is a necessary choice for many, including Cameron.

While Elin Kelsey notes that “anger plus hope equals justice,” author and educator Niigaan Sinclair may argue that humour plus hope equals resilience. The presentation on his newest essay collection Wînipêk: Visions of Canada from an Indigenous Centre begins with a slideshow of Indigenous people posting and sharing images of themselves as mermaids and mermen along Manitoban lakes and rivers. The social media trend originated among First Nations in Manitoba following the release of the live-action 2023 version of The Little Mermaid, and the trend sparked nation-wide from there. “There is nothing, I repeat, nothing like seeing Indigenous men decked out in rainbows and fishtails and bras, sunbathing on rocks,” Sinclair says of his research on this lighthearted epidemic. “It’s one part hilarious, another lifesaving.” He interviewed one of the mermen, named Johnny Harper, who resides in Northern Manitoba’s St. Theresa Point, who told Sinclair that “humour is a big part of our resilience, and I hope this whole merman thing sends that message.”

Social media trends are not new among remote Indigenous communities, Sinclair notes, citing “ice jigging to snowdrift diving to reading the TRC report.” During the COVID-19 pandemic, First Nations would compete with others in flash mobs at community-run checkstops. In his talk, Sinclair notes how “we were the ones who took curfews, we were the ones who agreed to have our odometer recorded … It was Indigenous peoples who completely understood that there’s a much bigger thing at work here to save elders, to save people in the community.” Despite harboring the brunt of the pandemic, climate-induced natural disasters, and intergenerational traumas, Sinclair concludes that both humour and community are the keys to survival and to maintaining hope within Indigenous communities.

Merpeople themselves aren’t new to many First Nations either, being a crucial part of Anishinaabe folklore that represents the connection between the people and the environments they reside in. “Considering this, it’s not surprising that in the midst of terrible crises in Indigenous communities, suddenly dozens of mermen and mermaids emerge.”

All three talks from all three authors demonstrate the overwhelming power of hope in the face of multiple different problems, a tool which rewrites the narrative previously written. Sometimes the answer to problems outside one’s capacity is simply to believe in a better future, to maintain positivity in the face of overwhelming pain, or to don a fishtail and a wig.

Learn more about the Vancouver Writers Fest, including past and future lineups as well as upcoming Writers Fest-related events, at https://writersfest.bc.ca/